Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Pope Francis has been in a Rome hospital for a month, battling double pneumonia and its complications. His condition would be serious for anyone but could be more threatening for an 88-year-old man who had part of a lung removed as a youth and who stubbornly refuses to slow down. While the Vatican reported this week that he is improving, he may be so weakened that, some have speculated, he could decide to step down.

Either way, the fate of a pope remains of great concern among the world’s approximately 1.3 billion Catholics, and a source of heightened curiosity for those who see Francis as an increasingly lonely moral voice on the world stage and wonder what kind of pope will eventually succeed him.

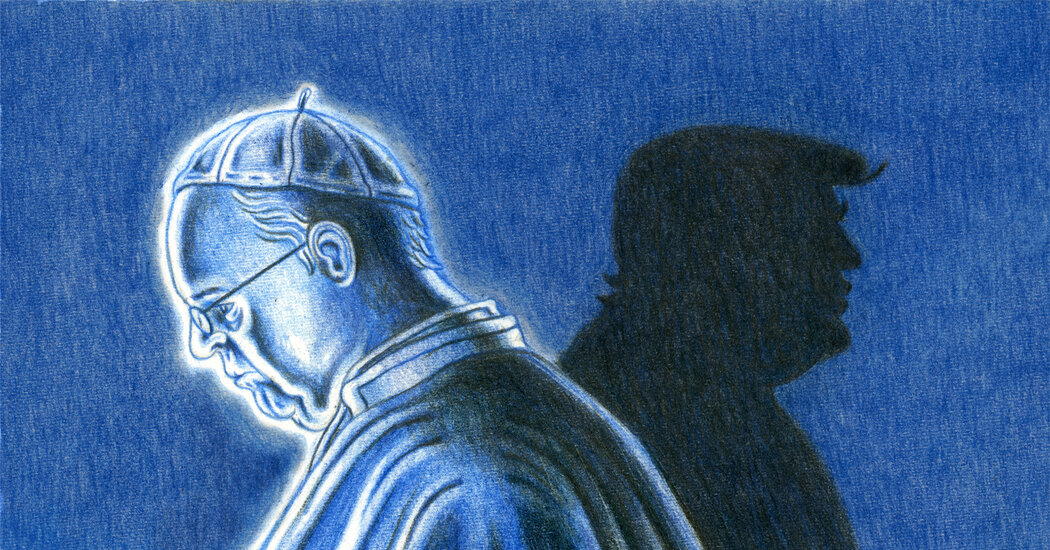

The yearning for a leader who puts the needs and interests of others — including the least powerful — ahead of his own is felt especially among the many Americans today who desperately seek a light inside the darkness of Donald Trump.

For this pope has emerged as an increasingly lonely moral voice against perilous global trends that have at times left the forces of liberal democracy reeling: nationalism, populism, disinformation, xenophobia, economic inequality and authoritarianism. A world without a pope like Francis will in some ways resemble a Hobbesian dystopia without both a prophet pointing to our better angels and a sensible idealist showing a better way.

Francis has become even more outspoken as those worrisome political trends accelerated, especially with Mr. Trump’s electoral victory. Shortly before the onset of his current illness, Francis took direct aim at Mr. Trump’s mass deportation policy and demonization of immigrants. “What is built on the basis of force,” Francis warned in an extraordinary letter to American bishops, “and not on the truth about the equal dignity of every human being, begins badly and will end badly.”

The pope proclaimed his vision almost immediately after he was elected 12 years ago this month as the first pope from the Southern Hemisphere, the first Jesuit pope, the first to take the name of the saint from Assisi. He traveled in the sweltering heat to the Mediterranean island of Lampedusa, where so many migrants have landed, or where their boats and bodies were lost, and celebrated Mass on an altar made from the wood of refugee boats.

Francis has also consistently denounced the destructive temptation of populism and the rise of “a myopic, extremist, resentful and aggressive nationalism.” On a 2021 visit to Athens he warned against the global “retreat from democracy,” a political system he called “the response to the siren songs of authoritarianism.” Unifying world powers in a shared battle against global warming has been a central theme of his papacy as well.

The pope is no starry-eyed moralist. “Reality is greater than ideas,” as he likes to say, and he is realistic about how the world works. He hates ideologies that hijack minds and hails the old-fashioned politics that gets stuff done. Politics “is a daily martyrdom: seeking the common good without letting yourself be corrupted,” he has told aspiring politicians.

Warning against “propaganda that instills hatred, divides the world into friends to be defended and foes to be fought,” the pope has forcefully pushed for both an inclusive church and an inclusive world. Like the Gospels, Francis was a D.E.I. exponent before that became a bad thing, and he remains convincing because he focuses on the moral core of what diversity, equity and inclusion mean, and why they are important. The keys are humility and mercy.

Read the pope’s remarkable address to a joint session of Congress in 2015: Francis channeled not just Catholics such as Thomas Merton and Dorothy Day but also figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln. “To imitate the hatred and violence of tyrants and murderers is the best way to take their place,” Francis said, adding, “We must move forward together, as one, in a renewed spirit of fraternity and solidarity, cooperating generously for the common good.”

Having a Roman pontiff as a bulwark of liberal values could of course be viewed as ironic. The Catholic Church until the middle of the last century was, officially at least, no champion of democracy or religious freedom or other principles that Americans, most notably, see as foundational.

Or used to. Now we have the pope promoting many of the rights and principles that much of America seems to be turning against. But this is where we are. “In this time of neo-imperial powers, I suspect that the Catholic Church is the best anti-empire — warts and all — that we have,” the Villanova theologian Massimo Faggioli recently said.

That slim hope hinges on who will eventually succeed Francis. Some Catholics (including key players in the U.S. administration) harbor fever dreams of a “Trumpian pope” who would purge the church of liberals and gays and anyone considered “heterodox.”

But there are no viable “papabili,” or papal candidates, in the Trump mold, and fewer political conservatives in the College of Cardinals — whose members elect the pope and have been largely appointed by Francis — than there were a few years ago. Mr. Trump’s bullying way of operating may even lead to a backlash among the cardinals, and a papal successor less friendly to Trumpist populism than there could have been a year ago.

The outcome of the next conclave could well be considered a political test for Mr. Trump and his movement, much as the conclave of October 1978 sent a message to the Soviet Union. In that election, the cardinals chose Poland’s Karol Wojtyla, a 58-year-old mountain-hiking cardinal from behind the Iron Curtain, who became John Paul II. “How many divisions does the pope have?” Stalin once asked when warned about offending the Vatican. Stalin’s successors learned the answer the hard way: John Paul II helped bring down Communism.

Of course, the delineation between good and evil is less clear today. The Soviet successor is authoritarian Putinism, which does not fit neatly into an East-West paradigm, and Francis, in a recent message from the hospital, lamented what he termed the world’s “polycrisis.” The solution will require what he once called an “artisanal path” to a handmade peace created by the daily actions and decisions of individuals.

This is a harder route in a seemingly more complicated post-Cold War world. But as Democrats flounder about for a message to counter Mr. Trump, they could do worse than listening to a pope who has been preaching one for more than a decade.

David Gibson is director of the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University and has covered the Vatican as a journalist for four decades.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Bluesky, WhatsApp and Threads.