Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

How to cite:

Wong M. Does Visible Light Cause Skin Damage? And How to Protect Against It. Lab Muffin Beauty Science. November 12, 2024. Accessed February 11, 2025.

https://labmuffin.com/does-visible-light-cause-skin-damage-and-how-to-protect-against-it/

There’s been increasing talk about how blue light from phones and computer screens could be a potential cause of skin damage. Is it worth worrying about, or is it just marketing? This topic is going to be a two-parter.

In this installment we’re going to talk about visible light damage, and how you can protect your skin; in part 2, we’ll talk about the amount of light that phones and computers produce.

Check out the video version of this post here!

Part 2 is located here: Will Blue Light from Computers and Phones Damage Your Skin?

When we protect ourselves from sunlight, we mostly think of sunscreens and UV. High energy UV rays from the sun are the main environmental cause of aging skin, and in light-skinned people, this is by far the biggest cause of skin damage.

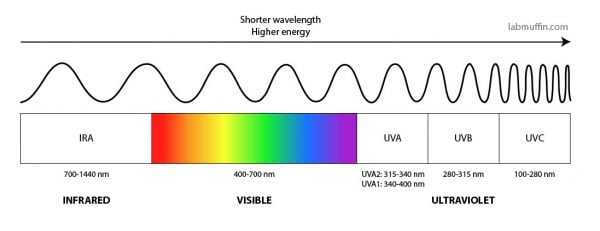

But UV isn’t the only type of light from the sun that can reach us on earth – the sun also produces longer, lower energy wavelengths of light in the visible (400-700 nm) and infrared (700 nm-1 mm) regions.

The energy from the sun that reaches the earth’s surface is around 3-7% UV, 44% visible light and 53% infrared (IR). UV causes disproportionately more damage because shorter wavelength means higher energy, so each photon (light particle) that hits your skin has more energy.

But newer research has been finding that the visible and infrared wavelengths can also cause skin damage too. Even though each particle has less energy, there’s a lot more of them, so it ends up being almost a “death by a thousand paper cuts” situation.

Shorter wavelengths of visible light that are closer to the UV range are the ones that have gotten the most attention, since they’re relatively more energetic and more damaging. In particular, it’s the wavelengths in the blue/purple region (400-500 nm) that have been found to be the most damaging. This shouldn’t really be surprising, since the divide between UV and visible light is pretty arbitrary, and is based on what our eyes can detect, not how our skin reacts.

Shorter wavelengths have higher energies, so blue and purple light is sometimes called high energy visible (HEV) light.

Related post: What Does SPF Mean? The Science of Sunscreen

The research on blue light isn’t as advanced as the research on UV, so we don’t know anywhere near as much about how exactly it causes damage to skin.

And to make it more confusing, older studies on the effects of blue and violet light aren’t as valid. A lot of the time the lights used in the studies also produced UV, so it’s possible that the effects they found were from the contaminating UV rays and not the visible light at all – and even very small amounts of UVA1 (0.5%) can work synergistically with visible light in causing its effects.

The sort of skin damage that visible light causes is quite varied…

Like with different parts of the spectrum, damage is all about wavelength within the visible spectrum. Different wavelengths of visible light can even have the opposite effects on the skin.

It’s possible that the different wavelengths of visible light could have effects that counteract each other as well.

So far it seems that blue-violet light is the most damaging, and can cause the production of nitric oxide (NO) free radicals. Free radicals are highly reactive substances with unpaired electrons that can react with substances in your skin and damage them, as I’ve discussed before. This damage causes cells to multiply less, collagen to break down and other microscopic changes, which could eventually lead to damaged-looking skin.

In people with darker skin, visible light can cause increased pigmentation, although this seems to happen in a way that doesn’t involve free radicals. This seems to be the only visible skin change caused by visible light so far though.

Related video: Video: My Routine for Fading Acne Marks (Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation)

While both blue light and UV can cause skin damage, it’s important to note that they cause different types of skin damage.

Related post: Chemical vs Physical Sunscreens: The Science (with video)

Even when the changes in the skin caused by UV and visible light overlap, it generally requires a lot more visible light to cause a similar change. Light energy is usually measured in these studies in joules per square centimetre (J/cm²).

In one in vitro study, there were greater changes in the level of free radicals (ROS), inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α) and collagen-degrading enzymes (MMP-1) with 6 J/cm² of UV light than with 180 J/cm² of visible light.

The amount of energy required to cause pigment changes in skin is also different. In one pigmentation experiment, 5 J/cm² of UVA1 caused the same amount of pigmentation as 40 J/cm² of visible light on volunteers with dark skin – in other words, 8 times as much visible light energy was required. In a different experiment, UV was found to be 25 times more efficient at causing pigmentation than visible light.

The smallest amount of visible light that caused pigmentation in all of the dark skinned volunteers in the same study was 40 J/cm². Since visible light from the sun hits the Earth’s surface at around 0.050 W/cm² in summer in Texas and 1 W is 1 J/second, this translates to around 15 minutes of sunlight.

How much visible light will affect your skin also depends on your skin colour. Bad news if you have darker skin – none of the tested amounts of visible light in one study caused pigmentation in people with light Fitzpatrick II skin, but people with dark Fitzpatrick IV-VI skin had increased pigmentation. One theory is that visible light interacts with melanin to form reactive oxygen species, which is why darker skin is more sensitive to visible light.

So now that you’re worried about visible light, how do you protect yourself from it? Unfortunately, sunscreen isn’t the answer. To protect from visible light, you need a visible product, and even sunscreens that contain “physical blockers” zinc oxide and titanium dioxide can’t protect from visible light, even when you put on a really thick layer (and if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll also know that these sunscreen ingredients work along the same lines as organic sunscreen ingredients anyway).

There are some other ingredients for protecting from visible light instead:

Iron oxide seems to be effective at absorbing all wavelengths of visible light and luckily, iron oxide is skin-coloured! It’s the main pigment in foundations and tinted moisturisers, and products containing iron oxide have been found to protect from pigmentation and improve the fading of melasma when it’s being treated with hydroquinone. Unfortunately there isn’t a standard measure of how well a particular foundation absorbs visible light, so it’s guesswork for now.

Antioxidants can reduce the effects of visible light. One study used a mixture of feverfew and soy extracts with gamma tocopherol (a form of vitamin E) on human volunteers and found that the free radicals produced were decreased by half.

The fact that you can see visible light is also helpful. While UV levels don’t necessarily match the amount of visible sunshine, we can see exactly how much visible light is hitting our skin! That means that we can use non-skincare methods of protecting our skin from visible light more effectively than for protecting skin from UV. Staying in the shade, and wearing hats and protective clothing will prevent visible light from damaging your skin, and won’t require as much guesswork or reapplication as skincare products.

Keep in mind that the research on visible light is still quite new, and the fact that it’s new should be reassuring. It’s taken this long to get around to researching it because UV causes the vast majority of damage. Visible light only causes a relatively small amount (and the only clinical effect so far is pigmentation in dark skin). We have lots of information already on how to protect ourselves from UV.

Chiarelli-Neto O, Ferreira AS, Martins WK, et al. Melanin photosensitization and the effect of visible light on epithelial cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e113266. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113266

Denda M, Fuziwara S. Visible radiation affects epidermal permeability barrier recovery: Selective effects of red and blue light. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(5):1335-1336. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701168

Duteil L, Cardot‐Leccia N, Queille‐Roussel C, et al. Differences in visible light‐induced pigmentation according to wavelengths: a clinical and histological study in comparison with UVB exposure. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(5):822-826. doi:10.1111/pcmr.12273

Kaye ET, Levin JA, Blank IH, Arndt KA, Anderson RR. Efficiency of opaque photoprotective agents in the visible light range. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(3):351-355.

Kleinpenning MM, Smits T, Frunt MHA, Van Erp PEJ, Van De Kerkhof PCM, Gerritsen RMJP. Clinical and histological effects of blue light on normal skin. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2010;26(1):16-21. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2009.00474.x

Kohli I, Chaowattanapanit S, Mohammad TF, et al. Synergistic effects of long-wavelength ultraviolet A1 and visible light on pigmentation and erythema. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1173-1180. doi:10.1111/bjd.15940<

Liebel F, Kaur S, Ruvolo E, Kollias N, Southall MD. Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(7):1901-1907. doi:10.1038/jid.2011.476

Liebmann J, Born M, Kolb-Bachofen V. Blue-light irradiation regulates proliferation and differentiation in human skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(1):259-269. doi:10.1038/jid.2009.194

Lohan SB, Müller R, Albrecht S, et al. Free radicals induced by sunlight in different spectral regions – in vivo versus ex vivo study. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25(5):380-385. doi:10.1111/exd.12987

Mahmoud BH, Ruvolo E, Hexsel CL, et al. Impact of long-wavelength UVA and visible light on melanocompetent skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(8):2092-2097. doi:10.1038/jid.2010.95

Ramasubramaniam R, Roy A, Sharma B, Nagalakshmi S. Are there mechanistic differences between ultraviolet and visible radiation induced skin pigmentation? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10(12):1887-1893. doi:10.1039/c1pp05202k

Regazzetti C, Sormani L, Debayle D, et al. Melanocytes sense blue light and regulate pigmentation through opsin-3. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):171-178. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2017.07.833

Vandersee S, Beyer M, Lademann J, Darvin ME. Blue-violet light irradiation dose dependently decreases carotenoids in human skin, which indicates the generation of free radicals. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:1-7. doi:10.1155/2015/579675